With the release of The Great Inception delayed by the printing company, we’re offering a couple more articles drawn from the book to tide you over until the truck arrives at the loading dock. – DG

Nimrod was second generation after the flood. His father was Cush, son of Ham, son of Noah.

In Sumerian history, the second king of Uruk after the flood was named Enmerkar, son of Mesh-ki-ang-gasher.

Enmerkar is also a compound word. The prefix en means “lord” and the suffix kar is Sumerian for “hunter”. So Enmerkar was Enmer the Hunter. Sound familiar?

Cush fathered Nimrod; he was the first on earth to be a mighty man.

He was a mighty hunter before the Lord. Therefore it is said, “Like Nimrod a mighty hunter before the Lord.”

Genesis 10:8-9 (ESV), emphasis added

The Hebrews, doing what they loved to do with language, transformed Enmer—the consonants N-M-R (remember, no vowels in ancient Hebrew)—into Nimrod, which makes it sound like marad, the Hebrew word for “rebel”.

Now, get this: An epic poem from about 2000 B.C. called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta preserves the basic details of the Tower of Babel story.

We don’t know exactly where Aratta was, but guesses range from northern Iran to Armenia. (Which would be interesting. Not only is Armenia located near the center of an ancient kingdom called Urartu, which may be a cognate for Aratta, it’s where Noah landed his boat—the mountains of Ararat. So it’s possible Nimrod/Enmerkar was trying to intimidate the people—his cousins, basically—who settled near where his great-grandfather landed the ark. But we just don’t know.) Wherever it was, Enmerkar muscled this neighboring kingdom to compel them to send building materials for a couple of projects near and dear to his heart.

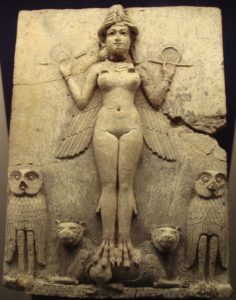

Some background: The poem refers to Enmerkar’s capital city Uruk as the “great mountain”. This is intriguing, since Uruk, like most of Sumer, sits in an alluvial plain where there are precisely no mountains whatsoever. Uruk was home to two of the chief gods of the Sumerian pantheon, Anu, the sky god, and Inanna, his granddaughter, the goddess of war and sex. (And by sex, we mean the carnal, extramarital kind.)

While Anu was pretty much retired (like the later Canaanite god El), having handed over his duties as head of the pantheon to Enlil, Inanna played a very active role in Sumerian society. For example, scholars have translated ritual texts for innkeepers to pray to Innana, asking her to guarantee that their bordellos turn a profit.

Apparently, part of the problem between Enmerkar and the king of Aratta, whose name, we learn from a separate epic, was Ensuhkeshdanna, was a dispute over who was Inanna’s favorite. One of the building projects Enmerkar wanted to tackle was a magnificent temple to Inanna, the E-ana (“House of Heaven”). He wanted Aratta to supply the raw materials. Apparently, this wasn’t only because there isn’t much in the way of timber, jewels, or precious metal in the plains of Sumer, but because Enmerkar wanted the lord of Aratta to submit and acknowledge that he was Inanna’s chosen one. And so Enmerkar prayed to Inanna:

“My sister, let Aratta fashion gold and silver skillfully on my behalf for Unug (Uruk). Let them cut the flawless lapis lazuli from the blocks, let them …… the translucence of the flawless lapis lazuli ……. …… build a holy mountain in Unug. Let Aratta build a temple brought down from heaven — your place of worship, the Shrine E-ana; let Aratta skillfully fashion the interior of the holy jipar, your abode; may I, the radiant youth, may I be embraced there by you. Let Aratta submit beneath the yoke for Unug on my behalf.”[i]

Notice that Inanna’s temple was, like Uruk, compared to a holy mountain. And given the type of goddess Inanna was, the embrace Enmerkar wanted was more than just—ahem—a figure of speech.

To be honest, some of the messages between Enmerkar and Ensuhkeshdanna about Inanna were the kind of locker room talk that got Donald Trump into trouble during the 2016 presidential campaign. But I digress.

Well… no. Let’s continue with the digression for a minute. We should stop for a brief look at Inanna’s role in human history. The goddess has been known by many names through the ages: Inanna in Sumer, Ishtar in Babylon, Astarte in Canaan, Atargatis in Syria, Aphrodite in Greece, and Venus across the Roman world. Let’s just say the image we were taught of Aphrodite/Venus in high school mythology class was way off.

Since we’d like to keep this a family-friendly book, we won’t dig too deeply into the history and characteristics of Inanna. Scholars don’t completely agree on the details, anyway. But it’s safe to say Inanna wasn’t a girl you’d bring home to meet your mother.

In fact, she wasn’t always a girl, period. You see, while Inanna was definitely the goddess with the mostest when it came to sex appeal, she was also androgynous. She was sometimes shown with masculine features like a beard. On one tablet (although from much later, in the first millennium B.C., almost three thousand years after Nimrod), Inanna says, “When I sit in the alehouse, I am a woman, and I am an exuberant young man.”[ii] Her cult followers included eunuchs and transvestites, and she was apparently the first in history to make a practice of sex reassignment:

She [changes] the right side (male) into the left side (female),

She [changes] the left side into the right side,

She [turns] a man into a woman,

She [turns] a woman into a man

She ador[ns] a man as a woman,

She ador[ns] a woman as a man.[iii]

It’s wonderfully ironic. The 21st century progressive ideal of gender fluidity was personified more than five thousand years ago by the Sumerian goddess Inanna, a woman who craved sex and fighting as much (or more) than men, taking on all comers in love and war, and better than men at both. Her personality is celebrated by modern scholars as complex and courageous, transcending traditional gender roles, turning Inanna into an icon of independent man/woman/other-hood.

There is an ongoing debate among scholars as to whether the priesthood of Inanna was involved in ritual sex. The concept of divine marriage was common in ancient Mesopotamia, but generally the participants were a god and his consort. It appears that the rituals were intended to please the god so he’d be receptive to the requests from a city or kingdom under his protection.

However, as a harimtu, which might mean “temple prostitute” or may simply refer to a single woman, Inanna herself participated in the rite with a king. And since she was the dominant partner in the ritual coupling, gender roles might not have been as clearly defined as we would assume.

From a Christian perspective, however, Inanna isn’t complex at all. She’s a bad Hollywood screenwriter’s idea of a 15-year-old boy’s fantasy woman. Inanna is selfish, ruled by her passions, and destructive when she doesn’t get her way. The Sumerian hero Gilgamesh, who ruled Uruk two generations after Enmerkar, is remembered partly for rejecting Inanna. As he pointed out in the story, every one of the men in her life suffered horrible consequences—for example, Dumuzi the Shepherd, who ruled as a king in Bad-Tibara, the second city in Sumer to exercise kingship after Eridu.

In the myth, even though Inanna married Dumuzi, she was happy to throw him under the bus when demons tried to drag her younger son, Lulal (Bad-Tibara’s patron god), down to the netherworld. At Inanna’s urging, the demons spared Lulal and took Dumuzi instead. Dumuzi’s sister pleaded for him, so Inanna agreed to allow her to take his place for half the year, thus making Dumuzi the first of many “dying and rising gods” in the ancient Near East.

More than two thousand years later, one of the abominations God showed the prophet Ezekiel was women at the entrance of the north gate of the Temple weeping for Dumuzi, called Tammuz in the Bible.

Well, for his impudence at daring to remind Inanna about the fate of Dumuzi, and the other poor shlubs who’d succumbed to the charms of the wild goddess, she flew up to heaven in a rage and demanded that her father, the sky god Anu, unleash the Bull of Heaven on Gilgamesh. That didn’t go well for the Bull of Heaven, but sadly for Gilgamesh, his best friend Enkidu was killed by the gods as punishment for spoiling Inanna’s revenge.

We shared all of that with you to make a point: This is the deity Enmerkar/Nimrod wanted to make the patron goddess of his city, Uruk! (Replacing her father Anu, ironically.) Could it be that veneration of the violent, sex-crazed, gender-bending Inanna was responsible for Yahweh’s decision to stop Nimrod’s artificial holy mountain?

Well… no. Probably not. Inanna has enjoyed a very long run near the top of the Most Popular Deities list. And why not? Selling humans on the concept of sex as worship is easy.

Looking at the values of our modern society, it’s no stretch to say that Inanna is the spirit of the age. Gender fluidity is the flavor of the month among progressives in the West. The values of Inanna—immediate gratification and sex with whoever, whenever—are considered more open-minded, tolerant, and loving than the virtues of chastity, fidelity, and faithfulness introduced by Yahweh long after Inanna was first worshiped as the Queen of Heaven.

Ironically, this means that so-called progressive ideas about gender and sexual morality are actually regressive! The enlightened think they’re cutting edge, breaking new ground and smashing old paradigms, when in fact they’re just setting the calendar back to more than a thousand years before Abraham.

If Yahweh had genuinely intervened to put a stop to the cult of Inanna, she would be long forgotten, like Enki. And Miley Cyrus would be a freak, not a culture hero.

No, the transgression of Nimrod was much more serious. Besides building a fabulous temple for the goddess of prostitutes, he also wanted to expand and upgrade the home of the god Enki, the abzu—the abyss.

For more on that story, see Part 4 of this series, Babel, the Abyss, and the Gate of the Gods.

[i] Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G. “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta,” The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.2.3#), retrieved 12/17/16.

[ii] Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G. “A cir-namcub to Inana (Inana I),” The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.07.9&charenc=j#), retrieved 12/17/16.

[iii] Sjoberg, A.W. “In-nin Sa-gur-ra: A Hymn to the Goddess Inanna,” Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie 65, no. 2 (1976): p. 225.